EDO REFERENCE GUIDE

Enrich your visit to every temple, castle, and museum. Our guide provides the backstory on Edo's key people, events, and culture so you can appreciate every detail.

Index

U

Battle of Sekigahara: 関ヶ原の戦い

The Battle of Sekigahara occurred in 1600 in what is now the town of Sekigahara in Gifu Prefecture. It is one of the most famous battles in Japanese history, involving over 150,000 soldiers from both sides: the Eastern Army led by Tokugawa Ieyasu, who would later become the first shogun of the Edo shogunate, and the Western Army led by Ishida Mitsunari, who opposed him. Both armies’ commanders had served the Toyotomi clan, which ruled the nation. The Eastern Army’s victory in this battle allowed Tokugawa Ieyasu to seize political control, marking a turning point that led to the subsequent Edo period. Today, the historic battlefield site features the Gifu Sekigahara Battlefield Memorial Museum, with numerous historical sites scattered throughout the area.

Boshin War: 戊辰戦争

The Boshin War was a series of battles between the old shogunate forces and the new imperial forces, beginning with the Battle of Toba-Fushimi in January 1868. While Edo was spared of any large-scale battles due to the shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu (1837-1913) resigning, daimyo from parts of the Tohoku and Hokuriku regions formed the Ouetsu Reppan Domei, also known as the Northern Alliance, to oppose the new government forces. This led to fierce battles in Nagaoka (Niigata Prefecture) and Aizu Wakamatsu (Fukushima Prefecture), resulting in extensive casualties. Forces loyal to the shogunate surrendered at Hakodate (Hokkaido) in May 1869, with the war ending in victory for the new imperial forces. This led to the new Meiji government being recognized both at home and abroad as the ruler of Japan, and set the country on the path to modernization.

Bushi (Samurai): 武士(侍)

Samurai were the ruling class under the class system of the Edo period, and controlled farmers, artisans, merchants, and others. Originally, samurai were battlefield warriors who used force to control people.

The absence of battles during the Edo period meant that samurai, once warriors, no longer had opportunities to fight with swords. Consequently, most samurai transitioned from soldiers to bureaucrats, serving the shogunate and various domains. While they carried two swords—one large and one small—on their waists, the swords served as symbols of their status, and were rarely actually drawn.

Some warriors who armed themselves with brushes in place of their swords became highly educated and contributed to the development of culture and academics.

Yet, the sword was also the heart and soul of the samurai. Martial arts were considered to be an essential discipline of a samurai, and some worked hard at swordsmanship and other arts. During the turbulent era at the end of the Edo Shogunate, there were situations where those swordsmanship skills were put to good use.

Castle Town: 城下町

As the residences of the daimyo, castles also served as the center of politics, with their vassals living in areas surrounding the castle. Merchants and craftsmen were also brought in from outside and settled to enhance its function as a city. It was in this way that castle towns were created. Many Japanese cities today can trace their origins to castle towns of the Edo period. Of these, towns like Matsue (Shimane Prefecture) and Hikone (Shiga Prefecture), along with their striking keeps that have been designated as national treasures, preserve the feel of castle towns of the Edo period.

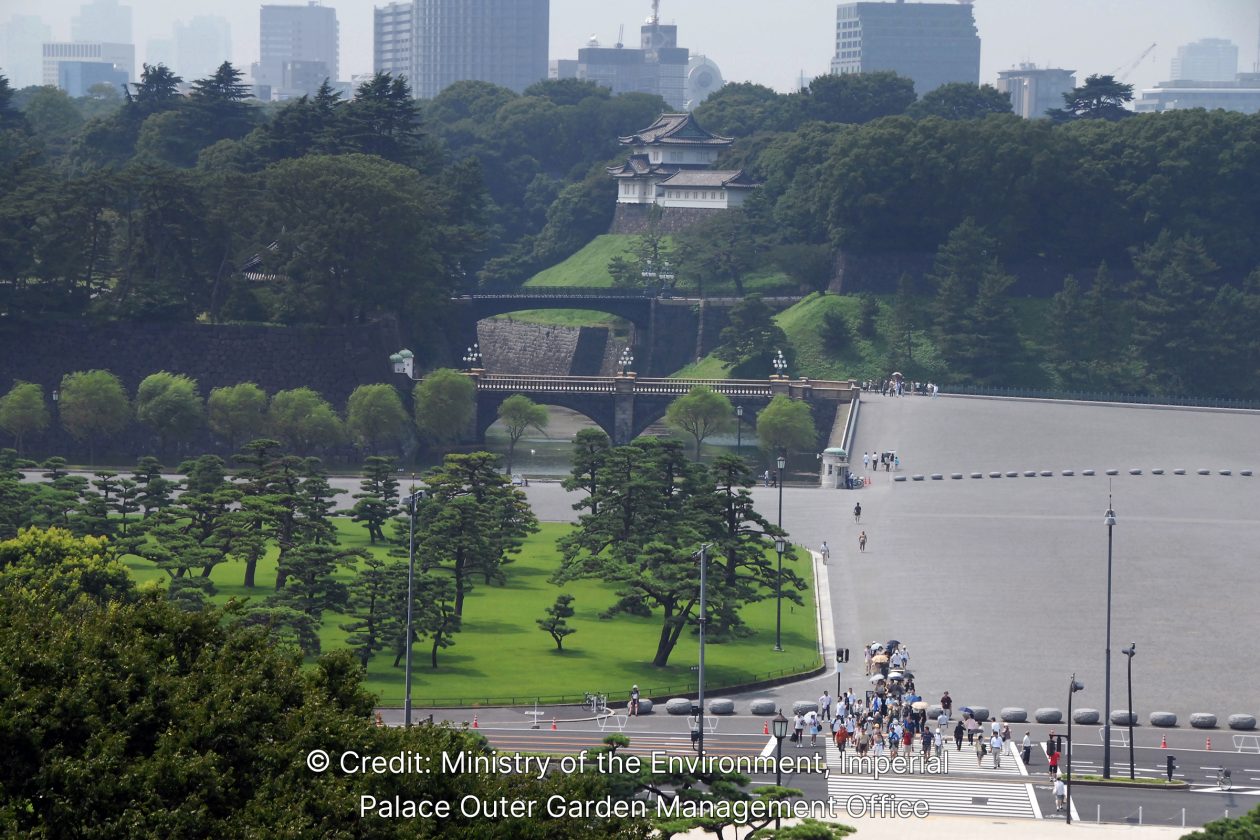

Castles: 城

Castles during the Warring States period were built on top of mountains or other locations that were easy to defend as military sites. Yet the growing role of government offices meant space for vassals to live was needed, so buildings were built on flat land.

Castles also became increasingly significant in demonstrating the lord’s authority to his subjects and neighboring lords. With the cessation of fighting into the Edo period, castles no longer operated as military facilities, and instead became political, economic and cultural centers.

Stonewalls, moats, keeps, and turrets served to defend against enemy attacks. Yet these gradually took on the role of giving the castle a more striking appearance, rather than any military significance. Moats were also used for water transportation.

The following 12 castles have existing keeps that were built before the Edo period, each allowing visitors to experience the grandeur of their past. Hirosaki Castle (Aomori Prefecture), Matsumoto Castle (Nagano Prefecture), Maruoka Castle (Fukui Prefecture), Inuyama Castle (Aichi Prefecture), Hikone Castle (Shiga Prefecture), Himeji Castle (Hyogo Prefecture), Matsue Castle (Shimane Prefecture), Bitchu Matsuyama Castle (Okayama Prefecture), Marugame Castle (Kagawa Prefecture), Matsuyama Castle (Ehime Prefecture), Uwajima Castle (Ehime Prefecture), Kochi Castle (Kochi Prefecture).

Daimyo/Han: 大名・藩

A daimyo was a samurai who was granted a fiefdom of 10,000 koku (1 koku = the amount of rice a person could be expected to eat in a year) or more by the Edo shogunate, and the domain ruled by a daimyo and its governing structure was called a “han.

Daimyo are divided into three categories: shinpan, fudai, and tozama.

- Shinpan: Shinpan daimyo were related to the Tokugawa shogun family.

- Owari domain(Aichi Prefecture), Kishu domain (Wakayama Prefecture), and Mito domain (Ibaraki Prefecture): Among the shinpan daimyo, these three domains were known as the Gosanke. The Gosanke were able to provide a shogun if there was no suitable successors in the shogun family.

- Fudai: Fudai daimyo were vassals of the Tokugawa dating back a long time, with one of the famed families being the Ii of the Hikone domain (Shiga Prefecture). Key administrative positions in the shogunate were held by the fudai daimyo.

- Tozama: Tozama daimyo were families that were originally rivals of the Tokugawa family, but submitted as vassals to the Tokugawa. Although tozama daimyo had large koku possessions, they did not generally hold roles in the shogunate administration.

- Kaga domain (Ishikawa Prefecture) and Sendai domain (Miyagi prefecture): representative tozama daimyo

- Satsuma domain (Kagoshima Prefecture), Choshu domain (Yamaguchi Prefecture), Tosa domain (Kochi Prefecture), and Hizen domain (Saga Prefecture): influential tozama daimyo and key players in the Meiji Restoration.

Dutch Learning: 蘭学

During the Edo period relations with foreign countries were strictly controlled. Particularly from the mid-17th to mid-19th centuries, official exchanges with European countries other than the Netherlands were forbidden. Consequently, European academic knowledge was brought to Japan in Dutch via the Netherlands. This is called “rangaku,” or Dutch Learning.

A variety of scholarly disciplines were introduced, including those useful in real life, such as agricultural technology and medicine, as well as mathematics, chemistry, astronomy, and geography to economics. Dutch learning greatly advanced scholarship in Japan.

Schools offering Dutch learning, such as Narutaki Juku opened by Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796-1866), a German physician who came to Japan as a doctor for the Dutch trading post in Dejima (present day Nagasaki City), and Tekijuku opened by Ogata Koan (1810-1863), who studied Dutch medicine, produced many talented people and helped to modernize Japan.

Edo Shogunate: 江戸幕府

The term “shogunate” originally referred to the military camps set up by the shogun during campaigns under his banner, but the term has come to refer to the samurai government led by the shogun. Among these, the Edo Shogunate (Tokugawa Shogunate) refers to the military government that ruled Japan for over 260 years from Edo (present-day Tokyo) as its base, with 15 successive shoguns following Tokugawa Ieyasu’s appointment as seii taishogun. It established a feudal system with the shogun at the top, ushering in a long era of peace.

In general, there have been three shogunates throughout Japanese history: the Kamakura Shogunate established at the end of the 12th century, the Muromachi Shogunate established in the first half of the 14th century, and the Edo Shogunate created at the beginning of the 17th century.

Gokaido(Five Routes): 五街道

The Five Routes refer to the five major highways constructed by the Edo shogunate. The Five Routes are:

- Tokaido Road: Connects Edo to Kyoto via the Pacific coastal region.

- Nakasendo Road: Connects Edo to Kyoto via an inland route.

- Nikko Kaido Road: Connects Edo to Nikko (Tochigi Prefecture).

- Oshu Kaido Road: Connects Edo to the Tohoku region.

- Koshu Kaido Road: Connects Edo to Kofu (Yamanashi Prefecture) and links up with Nakasendo Road.

The shogunate set up checkpoints at key points along these Five Routes to control the movement of people and goods.

The Five Routes, starting from Nihonbashi in Edo, were important not only for the movement of people, but also as a route for transportation for pack horses (horses that carry goods on their backs). The exchange of people, goods, and information, flourished along these routes, thereby promoting economic and cultural development.

Hanko (Domain Schools): 藩校

Domain schools were educational institutions established by feudal domains governing various regions during the Edo period, primarily to educate the children of their retainers. Many were founded in the late Edo period, focusing on Confucian studies and martial arts, though some provided unique curricula tailored to the domain’s characteristics or the times. Han schools produced numerous individuals who took on practical roles within the domains and also influenced the Meiji Restoration. Buildings such as the Kodokan in the Mito Domain (Ibaraki Prefecture) and the Chidokan in the Shonai Domain (Yamagata Prefecture) still exist today.

Japanese Gardens: 日本庭園

The emphasis on imitating nature is a fundamental aspect of Japanese gardens. They keep artificial designs such as straight lines, circles, and geometric patterns to a minimum, and instead express the wonder of nature within limited confines. To achieve this, Japanese gardens use a technique called “background scenery,” where distant mountains and forests are incorporated into the garden as backdrops.

The changing of the four seasons is a major appeal of Japanese gardens, where the masterful use of water is also of crucial importance. While chisenkaiyushikiteien, a garden style which featured a path encircling a pond for visitors to enjoy the water’s edge, became widespread, karesansui, traditional Japanese rock gardens designed to mimic water without its actual presence were also built.

During the Edo period, powerful feudal lords competed against one another by building gardens within their castles and residences. The “Three Great Gardens of Japan” —Kenroku-en in Kanazawa, Kairaku-en in Mito, and Korakuen in Okayama—are all daimyo gardens built by feudal lords during the Edo period.

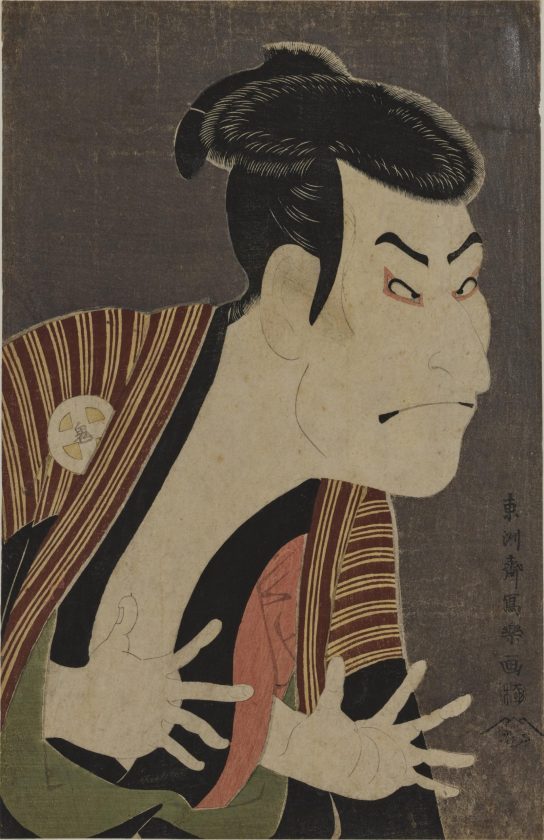

Kabuki: 歌舞伎

Kabuki was a popular form of performing arts among the people of the Edo period.

Kabuki has its roots in the “Okuni Kabuki” performed by a woman called “Izumo no Okuni” during the early Edo period. “Onna Kabuki” performed by women was banned due to offending public morals, and the resulting “Wakashu Kabuki” performed by young pretty boys in its place, was also banned for the same reason.

In the mid-17th century, older males took over these roles in “Yaro Kabuki,” which became the Kabuki of today.

Around the end of the 17th century, popular actors such as Ichikawa Danjuro I (1660-1704) came to prominence. Stories featuring heroes who roam around freely and perform with exceptional skill, as well as romantic tales vividly portrayed by male actors known as “onnagata,” gained immense popularity. In the mid-18th century, Kabuki further developed as a popular form of entertainment for the masses in Edo, partly due to the introduction of Ningyo Joruri (puppet theater performed by puppets instead of actors).

Kabuki began to draw larger crowds as theaters became larger and the stage sets more impressive. Kabuki actors became stars admired by all, their images spreading among the common people through Ukiyo-e, particularly actor prints (yakusha-e), and Kabuki went on as the forefront of fashion.

Katsushika Hokusai: 葛飾北斎

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) was an artist of the late Edo period. In addition to ukiyo-e, he also worked extensively in the field of book illustrations and left behind numerous works of art. He lived a long life and had a successful career, and his creative spirit remained vibrant even in his later years—at the age of 85 and 86, he traveled to Obuse (Nagano Prefecture) and created large ceiling paintings and other works. When he was 75 years old, he wrote passages like “At ninety I shall have cut my way deeply into the mystery of life itself. At a hundred I shall be a marvelous artist,” and he remained active for the rest of his life.

Katsushika Hokusai’s representative works include the “Hokusai Manga” and “Fugaku Sanjurokkei (Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji).” The former is an art book published as preparatory sketches for painting, and the latter is a series of ukiyo-e prints depicting Mt. Fuji, both of which were brought to Europe and had a great influence on impressionist and post-impressionist painters.

Kitamaebune: 北前船

During the Edo period, the transportation of goods was primarily over water. Water transportation had advantages because it could transport large quantities of goods at a time, whereas overland routes weaved through the domains of many hans, and were subject to restrictions like checkpoints and stoppages at rivers. Important shipping routes were established, including the “Nankai Route” linking Osaka and Edo, the “Eastern Sea Circuit” from the Sea of Japan to Edo via the Tsugaru Straits, and the “Western Sea Circuit” from the Sea of Japan to Osaka via the Kanmon Straits.

Kitamaebune were large ships that ferried goods to Osaka from the Sea of Japan side of Hokkaido and the Tohoku and Hokuriku regions on a western sea circuit. Some of the marine produce brought by the Kitamaebune from Hokkaido, such as kelp and dried abalones, were exported to China.

It was common for Kitamaebune shipmasters to purchase the goods and sell them in Osaka or other ports along the way, rather than charging shipping fees for transporting goods. This meant that there was a high risk for shipmasters, but they could also generate immense wealth from the trade. The Hokuriku region is still home to some of the residences of shipmasters who profited from the Kitamaebune trade in places like Mikuni Minato Port Town, providing glimpse into the prosperity of a bygone era.

Matsuo Basho: 松尾芭蕉

Matsuo Basho (1644–1694), a poet from the early Edo period, brought a refined artistry to fixed-form poetry, later known as “haiku,” which captured natural beauty and emotions by weaving seasonal elements into a 5-7-5 syllable structure. After his poetry studies in Kyoto, he settled in Edo. In 1689, he began a journey through the Tohoku and Hokuriku regions, eventually reaching Gifu Prefecture. His famous travelogue and poetry collection, “The Narrow Road to the Deep North,” documented this trip and remains widely read today. Basho’s legacy can still be felt in the Tohoku region, with traces of his travels visible in places like Yamanaka Onsen in Ishikawa Prefecture.

Meiji Period: 明治時代

The Meiji period is the period spanning from 1868, the year after the 15th shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu (1837-1913) resigned, to 1912 on the passing of the Emperor Meiji.

This was the era when Japan—which had been a loosely federated country divided into many hans during the Edo period—moved to a country with a modern, centralized government.

This major transformation from the Edo period to the Meiji period is known as the “Meiji Restoration.” The word “Restoration” meant “to change everything and become anew,” indicating the arrival of a new era.

Private Houses of the Edo Period: 江戸時代の民家

The most obvious difference in food, clothing and shelter of the people of the Edo period was their living environment. The location of the residence, the size of the land, and the prestige of the building were all determined according to class. The following are examples of typical residences:

- Thatched-roof houses: Farmers generally lived in houses with thatched roofs, but each region featured its own innovations to suit the climate. For example, the Gassho-zukuri styles of Shirakawago (Gifu Prefecture) and Gokayama (Toyama Prefecture) feature a thatched roof with a steep pitch for extra work space in the attic and to make removing snow easier. The houses of the highest class of peasants—those who led the people of the village—were constructed in a style similar to that of samurai residences.

- Tenement houses: Common people in cities usually rented small tenement houses of about 10 m2 to live in. Many of these tenement houses were made with board walls and shingle roofs, which could be destroyed if a fire broke out.

- Machiya (townhouses): Wealthy merchants built two-story buildings that served as both shops and residences, where they housed their employees.

The town of Edo was separated into overcrowded town areas and samurai areas with vast samurai residences. The Edo residences of influential feudal lords spanned some tens of thousands of tsubo (about 3.3 m2 per tsubo) in size. Rikugien (Bunkyo City, Tokyo), Koishikawa Korakuen (Bunkyo City, Tokyo), and Kiyosumi Garden (Koto City, Tokyo) are all trace their roots back to the vast gardens of Edo residences.

Shogun: 将軍

The head of the Edo shogunate, the shogun had the officially title of “seii taishogun,” or the supreme commander of the military forces tasked with subjugating factions that refused to obey the imperial court. This title was first held by founder of the Kamakura Shogunate Minamoto no Yoritomo in the latter half of the 12th century, and became the position held by the head of the samurai government.

Shrines: 神社

In Japan, there has been a long-held belief that gods reside in all things. Shrines served as places of worship for such deities and were closely intertwined with people’s daily lives. Natural objects, natural phenomena, and ancestral spirits, as well as mythological heroes and Buddhist deities, were also objects of worship. Real people were also enshrined as gods. Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of the Edo shogunate, was enshrined as the deity “Tosho Daigongen” at Toshogu shrines (such as Nikko Toshogu in Tochigi Prefecture) after his death.

While freedom of travel was not permitted during the Edo period, embarking on a journey to visit shrines was allowed, and it formed a source of great pleasure for the people. For many, a pilgrimage to Ise Shrine in Mie Prefecture was a once-in-a-lifetime journey, and systems were developed to help people save for the travel expenses.

Shukuba・Shukuba-machi(Post Towns / Post Stations): 宿場・宿場町

Shukuba were post stations established along the Five Routes and other important roads. Accommodations at Shukuba included honjin and waki-honjin for government officials such as for daimyo and samurai, as well as inns and cheap lodgings for common travelers. By the order of the shogunate, horses and men for transporting official goods were also available.

A Shukuba-machi, or post town, is a town that developed around these post stations. Narai-juku Post Town (present day Nagano Prefecture) and Magome-juku Post Town (present day Gifu Prefecture) along the Nakasendo Road, and Seki-juku Post Town (present day Mie Prefecture) on the Tokaido Road still retain the atmosphere of a post town during the Edo period.

Shukubo(Temple Lodging): 宿坊

Shukubo are lodging facilities provided for worshippers by temples and shrines. As pilgrimages to temples and shrines became popular during the Edo period (1603-1868), an increasing number of temples and shrines began to construct such shukubo.

Visitors can still stay at temple lodgings throughout Japan, including Mount Haguro (Yamagata Prefecture), Mount Oyama (Kanagawa Prefecture), and Mount Koya (Wakayama Prefecture), where some offer vegetarian cooking and Zen meditation experiences.

Temples: 寺院

Temples in the Edo period were not only places of Buddhist worship. As a means of prohibiting the spread of Christianity, the Edo shogunate made ordinary citizens belong to temples as parishioners to check that they were not Christian. The temples were also required to maintain logs that also served as family registers.

Famous temples also attract many visitors. Some temples became renowned for viewing cherry blossoms and autumn leaves, while others hosted a range of events. Stores catering to temple visitors opened up in front of the temple gates. Nakamise, located in Asakusa, remains a popular destination for tourists today. This shopping street has its origins in the Edo period, when it was established in front of the gate leading to Senso-ji Temple.

Tokugawa Ieyasu: 徳川家康

Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616) was a military commander who founded the Edo Shogunate. Ieyasu was born into a family of castle lords in Okazaki (present day Aichi Prefecture) and came to prominence as a Warring States daimyo (feudal lord). He then submitted to Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–1598) and became a great daimyo (daidaimyo) with possession of the entire Kanto region, with his residence at Edo Castle. Following the death of Hideyoshi, Ieyasu claimed victory in the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 and seized control of all Japan, receiving his appointment as shogun in 1603. He subsequently concentrated his efforts on creating a stable and peaceful society.

Ukiyo-e: 浮世絵

Ukiyo-e refers to paintings depicting the “ukiyo,” or “enjoyable, pleasant life,” and covers a wide range of styles—genre paintings, portraits of female beauties, actor prints, and paintings of landscapes. While Ukiyo-e also included brush paintings, it was mainly the woodblock prints that people enjoyed the most. Previously printed in black and white, “nishiki-e” was invented in the 1760s with bright multi-colored prints, and developed significantly as single complete images.

Landscape paintings by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), for example, were brought to Europe and greatly influenced painters such as Van Gogh and Monet. Ukiyo-e prints and other crafts drew attention in Europe when they were exhibited at the World Expositions in the mid-19th century, and played a role in the rise of Japonisme (influence of Japanese art).